In Conversation

Alejandro Cartagena, co-founder of Fellowship, discusses Joel Meyerowitz's unique photographic project, "Sequels," a narrative exploration of his unpublished 60 year archive.

Alejandro speaks to Joel Meyerowitz

Alejandro Cartagena: I know that you have been scanning your 250,000+ image archive in the past few years. I would love to know how the spark for the Sequels project came about. How does Sequels fit in within that revisiting of your career through this massive archive of unpublished works.

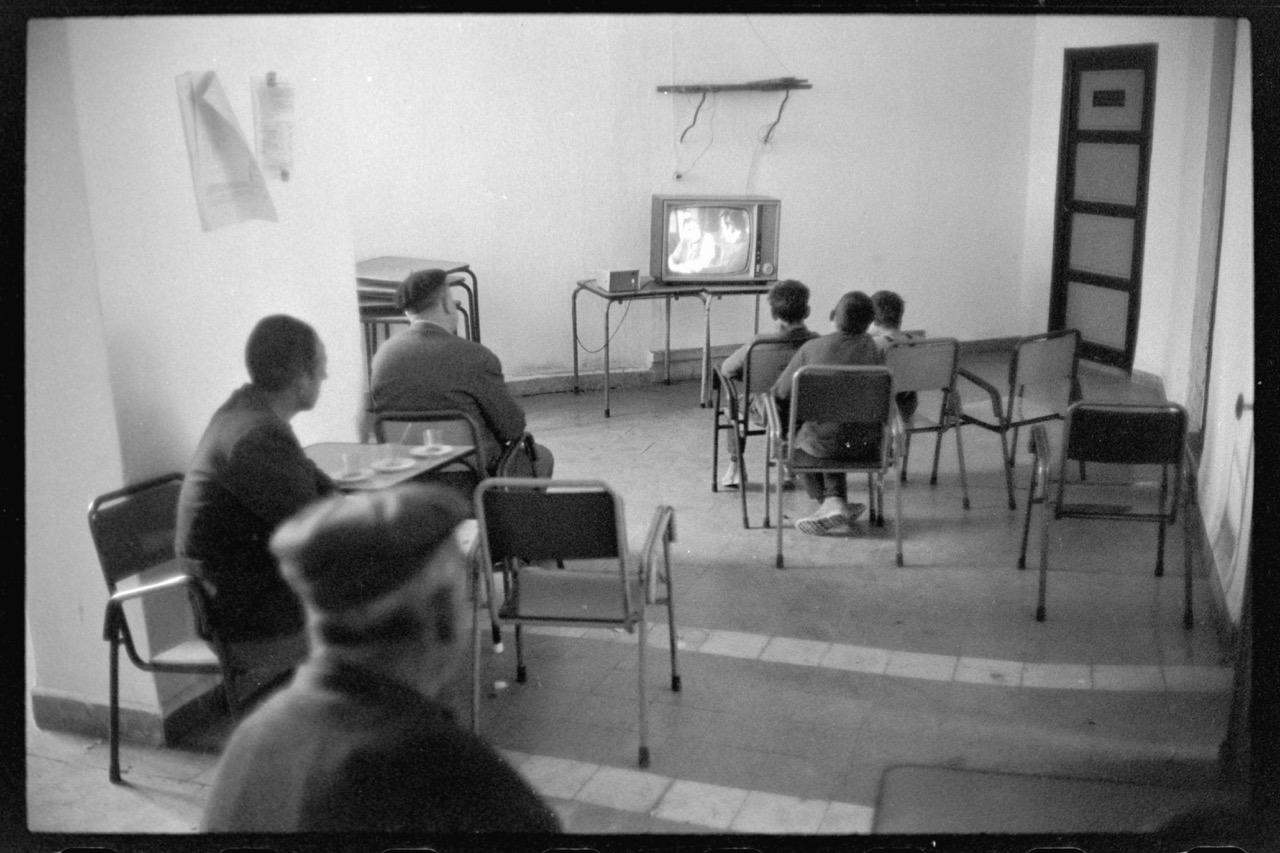

Joel Meyerowitz: To date, my studio has scanned over 250,000 images of my archive. The last batch corresponded to the 75,000 black-and-white negatives from the 10 or so years that I was shooting B&W, from 1963 into the early-mid 70s. For the first time, I could see all these rolls of film on a large scale on the screen instead of merely looking at them in a contact sheet, which was always a more difficult way of really seeing what was in the picture itself.

As I began to edit these photographs, I saw that there were remarkable, surprising and interesting connections between individual photographs. First, I saw the larger sequences of movement, and then I began to see interesting connections between things. Whenever I edit a book, I try to put provocative images in relation to each other so that it stimulates the viewer to have a fresh idea, not just about the content of the individual picture, but to see in the run of pictures, the artist's larger intention.

This is the skill of editing. It's what makes movies interesting to us because things are put together that don't normally belong there. But when we see them, the shock and surprise and pleasure we derive is what makes the medium interesting.

I'm trying to address this new generation of photographers to say we consider how photographs work in relation to each other. How can you stimulate your own visual ideas into becoming phrases? We think of photographs as single images, but in fact when you put a run of pictures together, you're making ideas, and whose ideas are they? They are your ideas, they are your identity. They become your language.

Joel Meyerowitz

Cartagena: This will be the first ever 10-year narrative photographic NFT project. How do you see this adding aesthetic, conceptual or narrative value to the photographic medium and your art practice?

Meyerowitz: Well, we're living in a time now where several billion people on the planet make photographs every day, and although 98% of those photographs or more come to no value whatsoever, there are people who have suddenly found how exciting and interesting photography can be.

I'm trying to address this new generation of photographers to say we consider how photographs work in relation to each other. How can you stimulate your own visual ideas into becoming phrases? We think of photographs as single images, but in fact when you put a run of pictures together, you're making ideas, and whose ideas are they? They are your ideas, they are your identity. They become your language.

So, I thought creating an online museum of my work could be engaging and exciting for people to look at and to anticipate what the next one is going to be like. I would use my personal approach to sequencing images, and have the ability with these new 75,000 scans to form 10 years of pictures. It's an exciting challenge for me personally, but I also hope for it to be an educational stimulus for everyone who looked at it.

In some way, these images that I made were reflections of my impulses, my instincts, my awareness; political, social, physical, sexual... All these human responses were made visible through both the photographs and then in finding ways of putting them together.

Joel Meyerowitz

Cartagena: How is editing and sequencing part of your art practice? How do you feel you learnt this magical talent of connecting images together?

Meyerowitz: I grew up in the era of comic books. Superman was invented in 1938, the very year I was born. My whole childhood was spent looking at and collecting all kinds of comic books and what are comic books, but movies in still frames, each frame in sequence with the next.

They tell stories. There are cliff-hangers, they're visually surprising, they're close-up and they’re far away. They have language in them, “POW!” and “Blam!” and “ka-BOOM!”, things like that. And so, as a child before there was television, there were these comic books, and sequencing in comic book form gave me a basic understanding of how to build drama, comedy, tragedy; all the expressive theatrical forms of telling a story were visible in the style of the drawings in a comic book and later, comic book art became part of Pop art in the early 60s.

I wasn't alone. In a sense, in my generation there were the Lichtensteins and Warhols of the world. They were using the same basic premise that they learned as kids, to imagine the image in a series of relationships. So, when I began to photograph and I got the work back, I always tried to see what was the current running through any given day on the street, or in any trip around America for that matter? What kinds of images told me about myself?

In some way, these images that I made were reflections of my impulses, my instincts, my awareness; political, social, physical, sexual... All these human responses were made visible through both the photographs and then in finding ways of putting them together.

Cartagena: When did you become aware that you had built an ‘archive’ of your work? Was there a threshold at which you saw your work collectively, rather than as individual ‘projects’?

Meyerowitz: I think it was quite early on, I would say around 1963 when I was really learning my chops at the time. I was learning how to behave on the street, how to make myself invisible, how to get close to people without them seeing or responding to me.

I was learning how to be both dynamic and stealthy at the same time, and I started going to the parades with my fellow photographer Tony Ray-Jones at the time, because the parades offered us some kind of camouflage.

The first really big body of work that I made had to do with attending these public spectacles; not photographing the spectacle itself but photographing the way crowds gathered, and the kind of human dynamism and energy in the crowds.

By reviewing my work based on the parades, I began to see a kind of archive of sensibility. And by reading this sensibility, I began to understand my identity. And once you understand something about your identity as an artist and a person, it's an easier step to knowing more about yourself and beginning to recognize these new interests that appear, because new interests grow out of the thing that you're working on.

So, I would say that way back in the early 60s was when I had my first sense that there was a ‘body of work’. That's what I would call it. I'm making a ‘body of work’.

Cartagena: Tell us about how you now, after scanning and reviewing your whole unpublished archive, see your photographic vision and how it developed over the years?

Meyerowitz: Well, the first thing I would say is that I see myself as an optimist. My work seems to have a very positive feeling about human behavior and human life. There's a lot of comedy in the work, and absurdity too. I watched the way people congregated together, the actions they took, the games they played, the social graces they expressed... all of these were fascinating things worth watching.

In a way, from my studies as a painter and as a graduate student in art history, I learned something about the kind of social realism that existed in America in the 30s. There was something about it that gave me a kind of foundation. It allowed me to look at the way life was depicted in a single work of art and how it had been drawn from real life, something of the essence of the moment. Photography is nothing but the essence of a moment.

Generally, I photographed at 1/1000th of a second, at somewhere around f8, a 1000th of a second means that the artist must be able to perceive in that fraction the potential for meaning, in a fleeting, fragmentary burst of human energy and activity. This, to me, is the highest level of photographic intelligence. To be able to have a perception about what might happen, and what that might mean if you were just in the right place at the right time.

But the NFT project with Fellowship will go on every day – for TEN years - each day a new and unexpected image. So, I would say the delight of the unexpected, the improvisational, is part of what makes this a question of: what's he going to come up with next? What kind of crazy relationship is possible here? And what might it mean?

Joel Meyerowitz

Cartagena: What are the ways in which the project will be edited to create a never-before-seen narrative?

Meyerowitz: As you can see from the initial images that are appearing in these first few weeks. I could have started at almost any point. But I started with a picture of the back end of a rocket at an air show in Paris in 1967. It seemed like the perfect metaphor for this project. And the next picture is a bunch of plates on the wall of a rectory of a church in Spain.

Why those two? Because the circles on the bottom of the Rockets jet engines related to the circles of the plates on the wall of this church. It's just a matter of feeling like, oh, what an interesting connection this is! And the next connection is a wall of rectangular framed objects and votives of people who have left images of themselves in gratitude to the church, and that attests to the healing powers of the church’s saint. But they're squares, so going from a circle to a square seemed like, oh, that's an interesting jump. It's another picture, but it's a picture in a different shape, and it's this kind of free-for-all, open-ended thinking and responding that makes linking images a very interesting discipline.

So, I'm going to continue in this first year, with the first 365 photographs, and from there we'll move on to 3650 works over a 10-year period. I think I can sustain this kind of playful relationship and see it through as the work changes over the 10 years of working in black-and-white. As these works changed, I was changing with them, and so in a way, this represents my own evolution. It's both playful and historical.

Cartagena: How does using NFTs for this project differentiate it from a photo book or exhibition output?

Meyerowitz: Well, a photo book or an exhibition is much more limited than the scope of this NFT project. A photo book, when you get beyond 60 or 80 images, starts to really wear you down. You better have something interesting to say in 60 or 80 images that lift the spirits and open – for ten years! - the mind and tantalize the eye. But a book, after all, is something you see all at once. You flip through the 100 pages and there's the book. Or for an exhibition, you go to the show, you walk through the show, and then you leave.

But the NFT project with Fellowship will go on every day – for TEN years - each day a new and unexpected image. So, I would say the delight of the unexpected, the improvisational, is part of what makes this a question of: what's he going to come up with next? What kind of crazy relationship is possible here? And what might it mean?

I'm sure that in every single case the viewer will have no idea: What could come next?